Apple’s defeat in last week’s anti-trust suit proves there’s something rotten at the tech-giant’s core, but the implications extend throughout the industry.

Apple’s fight with Amazon over e-books reveals its manipulation of prices and its unwillingness to surrender profit. Last week a US federal judge found that Apple had violated antitrust laws by conspiring with publishers to raise e-book prices. The case, which was brought by the US Department of Justice, has been followed by the publishing industry with a fanaticism not seen since Fifty Shades of Grey.

While five – Macmillan, Penguin, Hachette, HarperCollins, and Simon & Schuster – of the Big Six publishers accused of colluding with Apple settled before the trial, Apple gallantly decided to go it alone, insisting they’d done nothing wrong.

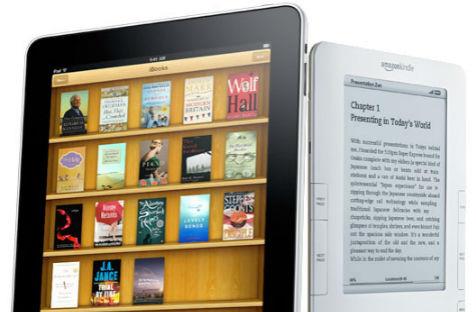

But they did, they broke the law. In 2010, Apple launched the iPad and iBookstore, elbowing its way into the ring with e-book heavyweight Amazon. Like the most unscrupulous pugilist, Apple had been making back room deals with bookies before the fight.

Meanwhile, Amazon had been buffing itself up by dealing with publishers under the wholesale model, which saw publishers selling books to Amazon for a set price, who were then free to sell it onto consumers for however much they pleased. To increase their market share, Amazon used the most basic tool of retail marketing – loss leading. Instead of selling e-books over the $12 to $14 dollars they paid publishers for the titles, they sold them at a loss, gaining a reputation for being the place to go for new books at $9.99 and a reported 90% share of the market.

The publishers still got their wholesale price and Amazon took the hit. Of course, this is a business strategy; one that Apple saw assuring Amazon a monopoly on the e-book market.

Publishers agreed, even though they liked the cash they received under the wholesale agreement. They knew that no one can trade at a loss forever, and when Amazon had secured enough of the market, the fear was that they’d leverage their position to make publishers lower their wholesale price. Consumers would still get $9.99 books, but publishers wouldn’t get to sell those books to Amazon for $12 or $14 dollars anymore. Their profits would drop.

Their profits would also drop under Apple’s battle strategy, but they were willing to give it a go. Apple was ready; they had an arsenal that included the Kindle-beating iPad and the new iBookstore. They had cash, they had resources, they had Steve Jobs. The only thing they didn’t have was a way to make profit while Amazon was selling the same wares below cost.

If they wouldn’t lower themselves to meet Amazon (they have the cash to do so but were unwilling to forego a profit), they’d bring the mountain to Muhammed and force Amazon to raise its prices. They did this by making a deal with publishers to adopt an agency model for e-books. This model sees publishers set the retail price of a book (opposed to a wholesale price), and then booksellers take a 30% cut, leaving publishers with 70%. This is less than what Amazon was paying, but it allowed for book prices to be over $9.99, which in the long run was seen by publishers as better for the rocketing e-book business.

So how do you get Amazon to agree to this? Collusion. The five publishers onboard with Apple individually approached Amazon and said, lift your prices to meet the agency model or we’ll withhold our best-selling titles. To get their hands on the newest bestsellers, Amazon agreed. Under US antitrust law, this collusion is illegal and lead to an increase in prices for consumers, which the laws are meant to protect.

Judge Denise L. Cote has stated:

‘The Plaintiffs have shown that the Publisher Defendants conspired with each other to eliminate retail price competition in order to raise e-book prices, and that Apple played a central role in facilitating and executing that conspiracy. Without Apple’s orchestration of this conspiracy, it would not have succeeded as it did in the Spring of 2010.’

But what does the ruling actually mean?

For publishers, at least for now, not that much. All of the five publishers accused of colluding with Apple settled out of court and agreed not to restrict a retailer’s ability to discount books. Basically, even before last week’s verdict, publishers had gone back to the wholesale agreement with Amazon, though retailers could no longer discount below the point of breaking even. No more loss leading, and now new release e-books only differ marginally between Apple and Amazon. For instance, Dan Brown’s Inferno sells on Amazon for $13.56 and through Apple for $14.99. Likewise, Neil Gaiman’s The Ocean at the End of the Lane is $15.39 (Amazon) and $16.99 (Apple).

That’s less than two dollars difference on both titles, Amazon is still cheaper, likely because of the purchasing power afforded by their market share, and people can be prudent when purchasing – they’ll go for the cheaper option despite the minimal saving. The publishers still get paid and the consumer has options, so the loser here is the same as it’s always been – other booksellers.

This is nothing new in the battle against Amazon, but the situation is getting worse. Two days before the Apple verdict was announced, Barnes & Noble CEO William Lynch resigned, his departure linked to the Nook e-reader’s inability to compete with Amazon’s Kindle and Apple’s iPad. Barnes & Noble also reportedly won’t name a new chief executive, a move the New York Times has interpreted as ‘signaling that the biggest chain of physical bookstores could be immediately broken up’.

In the same article, executive director of the Authors Guild Paul Aitkin made a comment about the Barnes & Noble situation that can be applied to any bricks and mortar store. ‘If the publishers colluded, it was to blunt Amazon’s dominance. Barnes & Noble’s troubles may stem form a misstep with its Nook tablets… but its precarious position is that of any rent-paying retailer facing a deep-pocketed virtual competitor.’

Further attempts to blunt that dominance have been seen recently with the merger of Random House and Penguin, with many in the industry predicting similar partnerships from other publishing houses in the future. While consolidating power might be good if you’re a huge company grappling with another huge company, it’s not great for literature.

By big publishers consolidating, there’s less competition. Penguin and Random house aren’t going to be bidding for an author’s manuscript anymore, which can result in dwindling advances and in turn limit financial security necessary for writers to write great books. As publishing houses become one entity and try to cut costs, those slashes can be made to editors, marketers and publicists, meaning a good manuscript may not get the attention necessary to make it great or known to the masses.

Publishers will also be less likely to take chances, throwing their money behind the Fifty Shades of Grey and Twilights of the world, leading to greater homogenisation of writing as the market panders to blockbusters and hot genres. Just look at The Cuckoo’s Calling, the acclaimed debut detective novel that hardly sold until it was revealed that JK Rowling penned it. One publisher is already kicking themself for being unwilling to take a chance on a talented yet unknown author. Now it’s rocketed to the top of best-seller lists because it’s been branded with Rowling’s name. Publishers follow trends, when one publisher unearths a hot property, the others will emulate with a similar offering, less publishers means less options.

It’s not just the consolidation of publishers that contribute to this; it’s the threat of losing bookstores like Barnes & Noble under the Amazon onslaught. In Brian X. Chen and Julie Bosman’s New York Times article, they indicate that the collapse of Borders lead to the growth of e-book sales tapering off, ‘as readers could no longer examine new titles before ordering them from Amazon’.

It’s a double-edged sword, bookstores can’t compete with Amazon, which consumers use as a library before buying online, and Amazon inadvertently relies on bookstores for consumers to browse titles. A similar online experience of browsing is yet to be developed, if that experience could ever be emulated digitally, though Amazon gave it a nudge by acquiring social networking and book recommendation site Good Reads.

J. B. Dickey, owner of the Seattle Mystery Bookshop succinctly summed up many of these issues:

‘If all of those corporate outlets vanish, there is suddenly a hell of a lot less space devoted to showcasing a large number of titles, we’ll probably see a continuing shrinking in print runs, maybe fewer titles published, fewer authors published and the New York houses retreating into the known best-sellers. Which means more novice and midlist authors scrambling to find a way to stay in print and more authors self-publishing their print books — or more likely releasing their works as e-files.”

While Amazon is also heavily invested in the self-publishing industry, this could become one viable alternative to the problems occurring in the publishing industry. Having shed the vanity press stigma, indie publishing is proving to be a bridge between authors and traditional publishers. Of course, it’s a lot of hard work to swim through the Internet’s self-published slush, but it’s possible, and in an industry that seems to be closing its ranks, increased options are invaluable.

Still, there are those that think all this bemoaning Amazon is really sour grapes, certainly amongst publishers, which could indeed be true. Amazon was carving out the e-book market in full view of all the other players for years. Its market share isn’t only because of loss-leading prices, it’s because Amazon is the market leader. Amazon began selling e-books in 2007, Apple didn’t enter the picture until 2010. If it wanted to compete, perhaps it shouldn’t have dragged its feet.

‘Apple did not conspire to fix e-book pricing and we will continue to fight against these false accusations,’ Apple spokesman Tom Neumayr has said. ‘When we introduced the iBookstore in 2010, we gave customers more choice, injecting much needed innovation and competition into the market, breaking Amazon’s monopolistic grip on the publishing industry.’

Apple’s reasons for appeal go beyond the e-book market. The judge’s ruling can be applied to content other than books, which means that Apple may be brought to task regarding its other digital properties, mainly music and films.