When I tell people I’m a poet, the most common response is an awkward surprise, as if I’ve told them I write hymns in Latin or build abacuses. Oh, that must be… interesting. Can you make a living out of that? As you can imagine, this response happens in Australia. Not in Ireland, where Seamus Heaney’s funeral was broadcast live on RTE radio and television. Not in India, where the words of Tagore, Ghalib and Lal Ded are woven through iconic songs and everyday conversations.

Australia is out of step with the rest of the world. Not only in taking serious, strategic action on the climate crisis. Or in embracing treaties with First Nations. Australia is out of step in terms of poetry and its place in society. In so many other places and communities, poetry carries the complex human mythologies, the enduring ideas that ground a people in their bodies and in the land. Poetry helps sustain and expand a sense of meaning that binds them together, while also carving out a generous, central space for otherness – both essential not just for a liveable now but for a liveable future.

Here, though, poetry seems to be relegated to the back of the bookshop on a low, narrow shelf, rarely surfacing in the public sphere outside of controversies over plagiarism, or in outbreaks of internecine conflict (‘a knife fight in a phone booth,’ as John Forbes famously characterised Australian poetry). I think one of the reasons for this, ironically, is the lack of official recognition of the public importance of poetry – the position of poet laureate. But, to borrow a familiar political slogan, it’s time.

An Australian poet laureate wouldn’t come out of nowhere, but would amplify hungers and ambitions that are already manifesting. In recent years, a number of similar initiatives, albeit on smaller scales, have begun. Last year, Monash University’s Climate Change Communications Research Hub engaged Amanda Anastasi as their Poet in Residence. Around the same time, The Saturday Paper named Maxine Beneba Clarke as their poet laureate, publishing a new poem of hers each week. After a year, Clarke handed the baton on to Omar Sakr, Ellen van Neerven and Paul Kelly. Similarly, in the midst of the pandemic, Melbourne’s City of Literature has commissioned a poet a week to write a poem in response to contemporary events.

Australia is out of step with the rest of the world … in terms of poetry and its place in society.

These initiatives recognise that poets have a unique contribution to make, especially on issues of public importance. Still, the audience and context of these roles are limited. An official national poet laureate is on another level of profile, recognition and responsibility.

Many nations with similar histories and politics, countries which Australia routinely compares itself to, have poet laureates. Not only in the United Kingdom and the United States, but in New Zealand and Canada. Not that this is a convincing argument in itself. North Korea and Germany’s Third Reich have had poet laureates. The position can take any number of forms, serving a wide array of possible purposes. The point is not to imitate others, but to find our own way. What are the dilemmas that are particular to this place, and what kind of poet laureate would make sense here?

Read: Authors speak on the power of language and art

I want to make an argument for an Australian poet laureate who is a paradox – who is both highly visible, and resistant to ideas of fame, both official and grassroots. An Australian poet laureate would fail dismally if it were supposed to be “representative” of “the real Australia”, as if such a thing were possible or desirable. Our national stories are for the most part either mirages or embody the dangerous myths of colonialism, ableism and masculine privilege. Instead, what if a poet laureate spoke out of the gaps in our public conversation? What if they could listen to that ‘whispering in our hearts’ and amplify and clarify it?

I won’t make any suggestions as to which particular poets might best be able to do this, but I’d endorse Joel Deane’s sentiment from his 2019 Peter Steele lecture (which itself is a profound argument for the power of poetry). He said, ‘right now, the Australian poetic voices that shine the brightest predominantly belong to female, multicultural or Indigenous poets.’

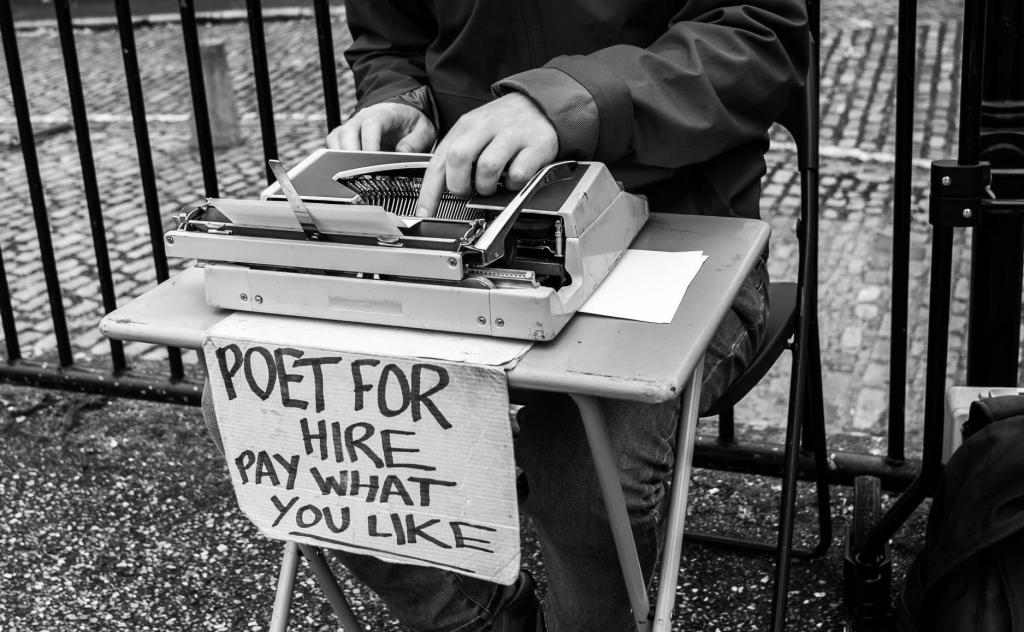

Clearly, the poet laureate needn’t be about writing poems for royal weddings or the AFL Grand Final. They might tour the country, taking poetry-writing workshops for people with disabilities, for incarcerated people, for the elderly, or for workers. They might, as Robert Pinsky in the USA did in the late 1990s, ask members of the public to be filmed reading their favourite poem. Certainly, I expect a poet laureate would want to write new poems, to make their own timely responses to our shared predicament, and have those poems reach the public.

The poet laureate might tour the country, taking poetry-writing workshops for people with disabilities, for incarcerated people, for the elderly, or for workers.

The ability of a poet to have a genuine impact on the broader culture will no doubt depend on how the role is conceived and instituted. Any poet laureate shouldn’t be appointed or managed by the Minister for Communications, or even by the Australia Council for the Arts. Poetry deserves to be detached from conservative or bureaucratic oversight, from demands to be “useful” or “balanced”. There are many institutions and organisations that would be more suited – the ABC, Australian Poetry, the National Library (as well as state and local libraries), to name only a few. Whoever the decision-makers are, it is critical they are independent, widely respected, and connected to local communities.

I can’t pretend to be unreservedly enthusiastic about this, though. There are risks in establishing a poet laureate position. Would they be the target of trolling and opposition? Would it trigger the sensitivities of those writers with a sense of privilege, who feel they deserve it more? Would the current political environment make it difficult to write courageously and organically?

Then there are the broader challenges. We would benefit from having a poet laureate, but it is also absolutely crucial to continue the struggle to foster literary, artistic and social ecosystems. Publishing, arts funding, the social safety net, the NDIS, bookstores – all these are increasingly threatened. Many are already writing persuasively of what might need to be done – Alison Croggon, Jinghua Qian, and Esther Anatolitis, for example.

The pandemic – the health crisis and the economic upheaval – has reminded us not only of our vulnerability and interconnectedness, but of the essential value of creative thought. Australia is currently constrained and fractured in so many ways by our history and our politics. Things need to change, radically. A poet laureate is not ‘the answer’, but they would concentrate our attention, help us make long-neglected connections, and nourish our courage.