Image shutterstock.com

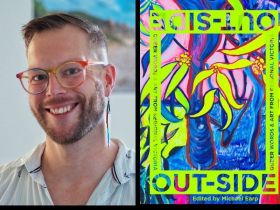

Brisbane-based curator and writer, Tess Maunder takes humidity and climate change as an astute metaphor for how we manage what has become an antiquated concept of multiculturalism and regional dialogue.

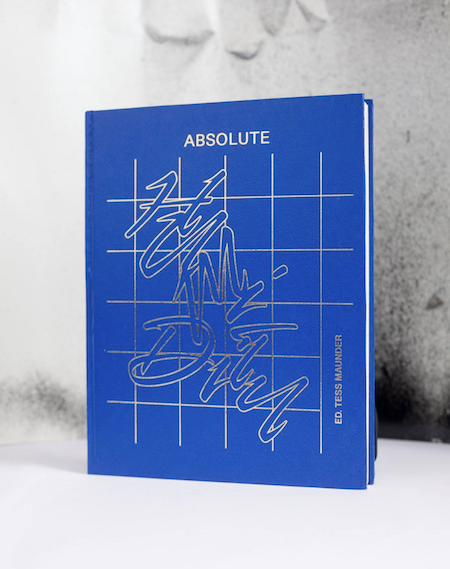

Maunder was the 2017 recipient of the Asialink Arts Creative Exchange to Manila, Philippines, and completed a residency at the International Studio and Curatorial Program in New York (also in 2017), an outcome of which was the recently unveiled Absolute Humidity, a publication that aims to re-position conversations about the climate – both theoretical and actual weathers of the region – by placing artist’s voices at the centre of the discussion.

She writes: ‘Absolute Humidity manifests as a sweaty brow. We might try to wipe it away with the back of our hand, blot it out with foundation in a bathroom mirror, or swim it away in the ocean. These attempts are futile. If the conditions are present, the sweat will return, again and again.’

Maunder explained: ‘I wanted to engage with the idea of the “para-curatorial”, to think about what happens when we reduce curatorial activity right down to its core function – a conversation…Should curators be striving to listen more – to their collaborators, the artists they work with, their stakeholders?’

‘Absolute Humidity is a collective framework that engages with the conditions that many artists are working under today: transnational relationships, ecological threats, exploitation, anxiety, sovereignty, politics, identity, disputed territories, and, around it all, the shifting weather.’

Maunder navigates the reader through thirty conversations with artists practicing in the Asia-Pacific region – from Jakarta via Brisbane, Ho Chi Minh and Mumbai, Hong Kong to Dubai to Los Angeles and beyond. It is a fascinating line up that seemingly hopscotches or slides across territories, in a progressive – and often collaborative – journey.

These essays are at once intimate – an artist’s journey with their making and cultural positioning – and yet capture a much broader pulse of a shared conversation that has largely not been had to date – a conversation that it is not built on Western or Australian perspectives of place (aka how position people), but a more nuanced and responsive engagement – a bit like the weather itself.

A good example is the conversation between Persian Pacific artist Léuli Māzyār Lunaʻi Eshrāghi with El Salvadorian artist Lucreccia Quintanilla, which explores the exoticisation of the “other”. It makes the obvious – but largely overlooked – point:

Quintanilla posed: ‘The assumption is always that “diverse communities are not able to represent themselves and need mediation. This is completely wrong and based on inclusion/exclusion binaries that need to be avoided.

‘Clearly many artists of all backgrounds live and work in Australia. Whether or not they directly make work about their communities, I would argue that they are, by default, still engaging with their culture.’

Eshrāghi responded: ‘I think audiences expect complexity and diversity on walls, stages and screens. We are all suffering from a dumbing-down of cultural content and delivery.’

Quintanilla and Eshrāghi offer an interesting flow where international, regional, national and local all blur into one. It is a pattern repeated across this book, and it offers incredibly insightful learning for those working in the visual arts and museum sector today.

photographer Czar Kristoff from Absolute Humidity’s publisher Hardworking Goodlooking

The need to move beyond utopian thinking

RAQS Media Collective (Monica Narula, Jeebesh Bagchi & Shuddhabrata Sengupta) encourages fresh thinking in their essay Wonderful Uncertainty: ‘The best kind of art, like the rain, invokes a reordering of the cognitive and sensory fields. It askes of its actual and potential publics to open doors and windows and let other worlds in.

‘This process is not only about what people “take away” from a work of art, but also about what they “bring forward” in their experience of it….The issue of not knowing enough about the “other” cuts both ways. It is not just publics that do not know their artist or what lies hidden in a work of art. Artists are equally susceptible to not exhaustively knowing their own work or sometimes not even minimally knowing their public.’

RAQS remind us in their text that ‘people bring their own histories, memories, scars and desires to bear on any work that they encounter. An artist cannot possibly know what these may be … In this sense, the artist is like someone who writes a letter to a lover they do not know they have, in a language they do not understand, without any guarantee that the letter will either reach its intended addressee or be opened and read, if indeed it ever arrives.’

They use a 1936 report as case in point, produced by a committee set up to examine the condition of museums in India. It complained that the foremost museological problem in India was the fact that vast hordes of illiterate people flocked to museums not to “know” but to “wonder”.

Have we lost the capacity to wonder? Have we become too caught up in knowing and categorising that we have forgotten how to be human together?

Eshrāghi adds to this point: ‘My plural cultural inheritance grounds me to know and live beyond the surface detail of identity politics, beyond stereotypes and nationalism. We create and maintain in-between or liminal spatial relationships in the ways that we know and make artwork, interplaying languages and cultural practices.’

Eshrāghi believes that multiculturally, culturally and linguistically diverse structures, are limited by mainstream understanding and consumption.

Quintanilla said: ‘Without sounding utopian here, I would say that in terms of potential models that are culturally productive and reflective we have a few already. And there should be more. We should have artist run spaces in our sheds and lounge rooms! At an institutional level, we need more curators like you [Maunder] around – curators who aren’t afraid to touch cultural complexity, with all the potential miscommunications that this might bring.’

‘There needs to be less fear on both sides. There is an anxiety that you need to fit in with Western Art historical frameworks but this can be a dead end road when there is a more dynamic dialogue to be had,’ said Quintanilla.

She makes that point that we ‘should be able to see the world in its multiplicity as audiences here within Australian arts institutions.’

Climate Change is more than weather

In the other essays, Maunder poses a suite of questions to contributing artists: ‘Has the weather ever changed the process of a work you have produced? What do you think is the most urgent issue for the global community in terms of creating real change?

What do you think curators and art professionals could improve when engaging with decolonial politics?’ And the persistent question, ‘What do you think we should be doing to address climate change?

Artist Bonita Ely offers a luminary solution: ‘Just as there’s a superannuation scheme in Australia supported by compulsory employer/employee contributions, so we could establish a national trust fund to support environmental change…’

Climate change is not just environmental in these essays, but also social, political and economic as it impacts how artists work – are perceived and presented – and the kind of storms brewing on the horizon.

Artist Tintin Wulia sums it up perfectly in her interview: ‘The last two centuries have seen revolutionary developments whereby humans can now experience extreme “connection” (for example through digital media and the Internet) and extreme disconnection at the same time (for example, the rise of nationalism and the mechanisms like border-ing and passport-ing systems, as well as the polarization of our civil society).’

What Wulia – along with the very real and generous stories of the other contributing artists in Absolute Humidity – point to is a shared contemporary reality. It may be sticky and hard to deal with like tropical humidity, but it is persistent, renewing, and life giving.

Absolute Humidity(2018) is published by Hardworking Goodlooking (Manila/New York) with support from the Australia Council for the Arts and Arts Queensland.

To get your copy visit https://absolutehumidity.bigcartel.com/

Absolute Humidity includes contributions by Alfredo and Isabel Aquilizan, Angela Tiatia, Ayesha Jatoi, Bahar Behbahani, Bonita Ely, Brenda L. Croft, Brian Robinson, Chantal Fraser, Drew Kahu’āina Broderick, Elisa Jane Carmichael, Gulf Labor, Hitman Gurung, Ho Rui An, Joy Lehuanani Enomoto, Karrabing Film Collective, Lantian Xie, Léuli Māzyār Lunaʻi Eshrāghi, Liu Yujia, Lucreccia Quintanilla, MAP Office, Okin Collective, Prasad Shetty, Raqs Media Collective, Ravi Agarwal, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Rupali Gupte, Sid M Dueñas, Sheelasha Rajbhandari, Taloi Havini, Tintin Wulia, Tita Salina, Trevor Yeung, Tuan Andrew Nguyen, and Zheng Bo.