In a long and diverse career, the Canadian novelist Margaret Atwood has experimented on several occasions with dystopian futures, an interest that has become a theme of several of her most recent books.

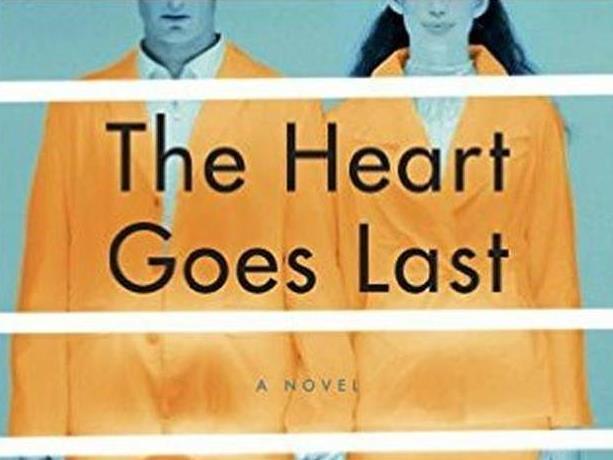

The Heart Goes Last is another confronting version of what the future could hold. Atwood imagines a world in which the American middle class has collapsed into a series of rust belt towns in which an ordinary couple named Stan and Charmaine are reduced to living in their car at the mercy of roving thugs.

In such an environment, people are willing to trade their freedom for a chance at reclaiming surburbia. They sign up to live in ‘Consilience’ (a portmanteau of Cons and Resilience), a town built on the full employment and guaranteed prosperity of a neighbouring prison Positron. The catch is that they only live in the town half the time – the other half they spend as prisoners trading places with ‘alternates’ who take their homes and lives every second month.

The prison is gentle, the food excellent and the whole set up apparently benign – as long as you play by the rules. But the corporation running the enterprise does not tolerate dissent and once a sexual adventure punctures the cling-wrapped surface of their lives truths are revealed forcing Stan and Charmaine into separate but interlinked high stakes scenarios of exposure and escape.

The Heart Goes Last is an imaginative and, of course well written, but quite conventional fable about totalitarianism in a privatised world.

Stan and Charmaine are a married couple struggling with the very ordinary challenges of maintaining a relationship far more than they are Winston Smiths with a cause to fight. They are perhaps a little too credulous, Charmaine in particular too willing and wanting to believe in the perfection of their new lives, but that is part of the comment Atwood wishes to make.

Atwood is not blatant in her politics – nowhere nearly as much as she was 20 years ago in The Handmaid’s Tale – a feminist dystopian work which is now a classic of the political future fiction genre.

She gives us real people we can believe in, convincing motivations, and plenty of humanity to keep us engaged as readers of characters not recipients of a lecture. The novel has a very satisfying structure – a well-balanced story arc that delivers a gratifying ending with a lovely kick in the final pages.

The darkest strain of the Positron Project – which cannot be given away in a review – is perhaps the least convincing, not woven tightly into the novel. But in a sense it doesn’t matter. The threat within the world of the novel is not so much what the corporation is getting up to so much as that it has the power to get up to whatever it wants.

This is a work which deals with the nature of freedom and our willingness to exchange liberty for comfort and to believe in authority figures who make us feel good.

It is not Atwood’s most complex or significant work but it is a worthwhile and engaging read from a master craftswoman.

The Heart Goes Last

by Margaret Atwood

Published by Bloomsbury

$32.99 Hardback