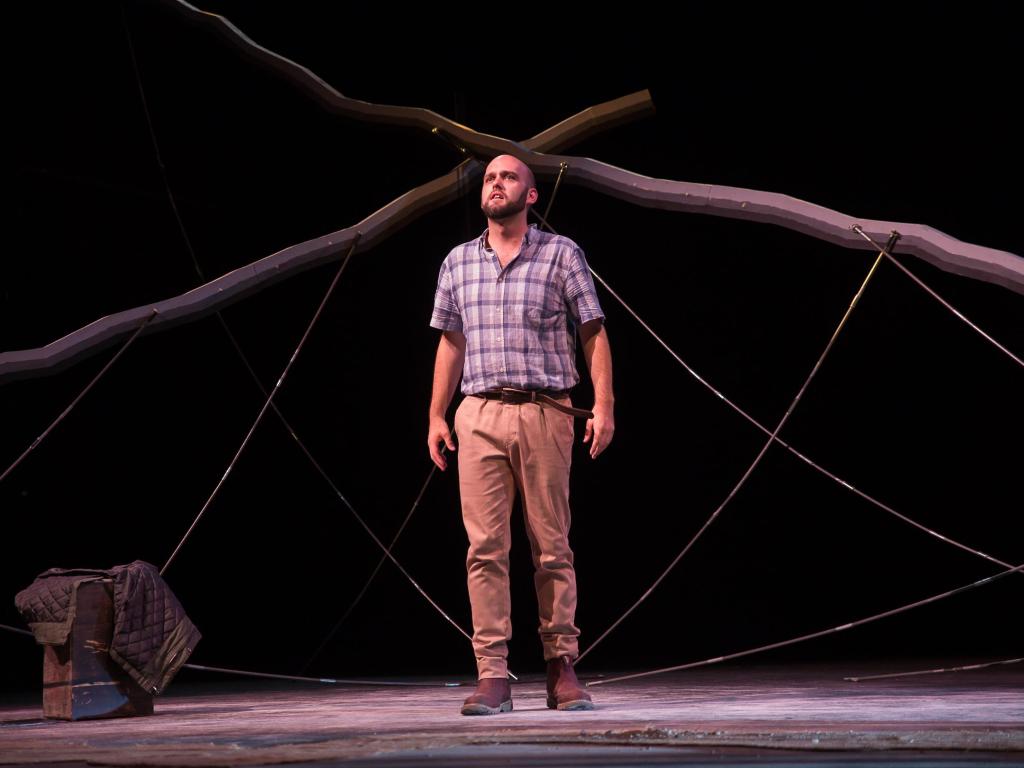

Image: The Weight of Light. Photo credit: Shelly Higgs/The Street Theatre.

Book launches make me want to vomit. My own book launches.

Of course, it is wonderful to have a crowd of people help celebrate your new book, but it’s also stressful. Will the speakers be entertaining? Will I make a fool of myself? Yes, launches make me feel sick; or, at the least, make me want to head for the hills.

Which is why, at the world premiere of The Weight of Light, a song cycle, in Canberra earlier this year, it was surprising to feel positively calm in the foyer before the performance: I drank mineral water, I chatted, I gave and received embraces, and all the while I was relaxed and happy. But then – but then! – the bells rang and the audience entered the theatre and as the lights went down I could feel my heart making bone-shaking explosions. How was the audience going to respond? Was the work inherently problematic? And why had I been so naïve to think I could produce a text to be sung?

Boom! went the thing in my chest.

Back at the tail-end of 2014, Paul Scott-Williams, the CEO and Artistic Director of the Goulburn Regional Conservatorium, approached me to write the libretto for a new song cycle with the music to be composed by James Humberstone. Paul wanted a brave new work that would present a story with contemporary relevance, one that might find new audiences for art song. Over coffee I told Paul that I was grateful – humbled, really – to be asked, but others were more qualified for the gig; I offered to recommend some prominent poets from our region. Paul would have none of my evasions. He had read The Beach Volcano, a novella of mine about a successful though flawed musician who was trying to navigate middle-age; he said he had found the story both moving and poetic. I protested: ‘But writing poetically doesn’t necessarily make me a librettist!’ Still Paul dug in. He knew of my long-standing love of music, my interest in masculinity, and what it means to be good; plus I was a local writer. ‘I really want you,’ he said.

Foolishly I said I would think about it.

Over the following summer I privately went through the pros and cons of the commission: it’s true that I have spent my life adoring a wide range of music, and collaborating with a composer as adventurous as James Humberstone would be a terrific opportunity; but, so I told myself for the umpteenth time, I have written a novel, with another, Bodies of Men, to be published by Hachette in 2019, three novellas, fifty short stories, and – wait for it – two poems. The evidence fell down on the side of ‘prose fiction’. That was my specialisation and I needed to, as they say, stay in my lane.

But where had the primacy of specialisation come from?

Has it not been the case for longer than most can remember that writers have been finding new ways to tell and share stories?

Perhaps, in Australia, it is arrogant to… well, make art full-stop. Pursuing a career as a footy player is fine; it is probably okay (according to some) if all you want to do is look after the family and put food on the table. But if you want to be an artist? That’s an indulgence. It is especially indulgent to want to make more than one kind of art. Best to be a plumber, or a soldier, but more about the latter in a minute.

Perhaps the blame for specialisation can also be put at the feet of arts funding. We are lucky in Australia to have government funding of the arts. While I don’t wish to critique the role of government support per se, public funding can result in artists specialising in form – the application process is about presenting a body of work, demonstrating industry relationships and peer recognition, all so we can trample over each other as we try to reach the top where there is money. Peer assessment, a process in which I have been involved at different levels, is the best way to assess grant applications, but it is not perfect. Might one of its imperfections be the imposition of specialisation?

At a more personal level is the fact that most artists doubt their creative worth. Having produced a half-century of short stories, it is probably a legitimate exercise for me to write another. Having published one novel and about to have a second in the world, it is possibly alright to call myself that mystical beast, a novelist.

But stepping into the world of libretto? That would be ridiculous.

Except it was not ridiculous. In the end, so I discovered, having eventually said yes to the commission, it was about creating a story: a character being tested through a series of scenes and relationships, in this case an Australian soldier returning home from his latest tour of Afghanistan with a dark secret only to discover that his family has a dark secret too. The libretti arose from the dramatic scenes, which involved reshaping my words into song lyrics; these were then handed to James to do whatever he thought necessary.

From my perspective, there was considerable rewriting, editing, reflecting, and writing some more; words – entire songs – were removed to make space for the music to breathe. I sought advice, primarily from national award-winning poet Melinda Smith. Slowly the overall work emerged. As commissioner, Paul had created a space where the song cycle could come to life organically, and James has been a warm and generous collaborator; also critical was the creative development process facilitated by Caroline Stacey at The Street Theatre in Canberra.

If I have learnt anything from working on The Weight of Light it is the importance of saying yes as often as possible, even when it is terrifying, and a part of that is having the confidence to risk failure. Ultimately the audience response to the Canberra performances was kind. One reviewer claimed, ‘What this song cycle shows is that if there is anything good to come out of war, it is the beauty of creations such as The Weight of Light.’

I have also learnt that taking risks can make you feel dangerously alive.

Nigel Featherstone and James Humberstone’s The Weight of Light has two performances at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music on Friday 27 July, at 1pm and 7.30pm. Visit sydney.edu.au for details.